Deep Encounter with Collective Trauma

A Personal Reflection from a Collective Trauma Integration Process

Introduction: Overview of the Collective Trauma Integration Process

The Collective Trauma Integration Process (CTIP) supports individuals and groups in integrating trauma that has been passed down through generations and are embedded in cultural systems—such as slavery, war, genocide, and racism. As Thomas Hübl teaches, these traumas live not only in our nervous systems, but also in our family systems and social structures.

Our Collective Trauma Facilitation Training (CTFT) group has been meeting for nearly a year and a half, working with personal, collective, and cultural trauma. Together, we’ve cultivated a relational field—one grounded in safety, presence, and mutual support.

We begin by engaging our personal traumas and gradually reflect on how they connect to larger collective patterns. Within the container of this shared field, unconscious layers of trauma can begin to surface and be held with care.

A CTIP involves recognizing and integrating the "frozen" or dissociated aspects of experience—both individually and collectively. In this process, our group resonance becomes a source of coherence, healing, and transformation.

Deep Encounter with Collective Trauma: A Personal Reflection from CTIP Training

I attended the fifth segment of the CTFT that took place in Germany with roughly 175 others, led by Thomas Hübl. What surprised me most was how deeply I was affected by a sincere, heartfelt apology.

I’ve read, for instance, about the Dutch government’s formal apology for its role in slavery—specifically to Suriname and the six islands of the former Netherlands Antilles. But I’ve often wondered whether such gestures are rooted in genuine remorse or political correctness. In Germany, what I experienced felt different.

I witnessed personal apologies from Germans whose ancestors were involved in World War II and the Holocaust. Participants with ancestral ties to the Americas (Turtle Island), India, Africa, Australia, and Asia shared powerful stories about the lasting effects of colonialism and racism on themselves and their families. In addition, individuals whose ancestors were — or may have been — perpetrators offered apologies that were specific, direct, and emotionally present. These apologies were addressed to those of us whose ancestors had suffered. And they resonated deeply.

When the focus was on World War II, I shared about family members who were in Japanese internment and POW camps. Later, a participant—I'll call him Neil—stood and acknowledged the entanglement of his Japanese ancestors with many of the people in the room, in the field. He offered a well-articulated, deeply sincere apology on behalf of the Japanese people for the atrocities committed through imperialism and colonialism across Asia.

He named countries: China, Korea, Indonesia, Vietnam, Cambodia, Burma—and the atrocities: the mass killings of civilians, the abduction and rape of “comfort women,” the occupation and violent suppression of local populations. Neil then named his beloved Japanese grandmother, who had lived in Japanese occupied China and had remained silent about that period.

In this work, when an ancestor is named, Thomas guides the group to open to past generations—allowing us to feel the presence of the ancestor, such as a grandmother—so the person apologizing can sense our connection. This opens a path for healing in the descendant, who carries the inherited impact of their ancestor’s actions.

As Neil began his apology, I unexpectedly burst into tears. Grief rose from a place I didn’t know existed. I felt my grandmother, grandfather, father, uncles—all standing behind me. While I had long known intellectually about my family’s trauma, I had never felt it this viscerally. My father and his parents had been imprisoned by the Japanese, yet they never spoke with hatred. I was aware of the war’s impact on my father but had never connected to it emotionally. The information went from 2D to 3D. Neil’s apology broke that open. I could feel the gratitude of my ancestors for this young man’s honesty and presence.

Historical Context

On January 1, 1942, the Japanese Imperial Army invaded the Dutch East Indies. The Dutch colonial government abandoned Jakarta, and Japanese troops took control of infrastructure, including ports and postal services. Thousands of captured Dutch soldiers were sent to camps across Southeast Asia and Japan. Around 65,000 Dutch and Indonesian troops were forced into labor, including on the Burma Railway and in Japanese mines, where many died from mistreatment and starvation. An estimated 80,000 Allied troops (Dutch, British, Australian, and American) became POWs, with death rates ranging from 13–30%. About 25% of Dutch-Indonesian POWs did not survive.

Over 110,000 civilians of Dutch descent were interned. Those who could prove Indonesian ancestry could sometimes avoid internment. Women and children were held in prisons or makeshift camps, separated from male relatives. Boys over age ten were confined in men’s camps. Internees were forced to surrender most possessions.

My grandmother was asked to join the resistance and worked closely with Captain Meelhuysen, who had gone underground after his plane crash. Despite precautions, too many people knew of their activities—those unsympathetic to the Dutch colonists and collaborating with the Japanese. The Kenpeitai (Japanese military police) waited until they had identified key figures and weapons caches. Meelhuysen and many others were arrested, and under torture, my grandmother’s name surfaced. Six leaders were sentenced to death and beheaded and Meelhuysen committed suicide.

My aunt, who lived with her mother at the time, wrote me her version:

Interrogations took place in Section 3 at Boeboetan, where Moes (my grandmother) was briefly held. I could bring her clean clothes weekly. The Sumatran commissioner leading the section once said, “Miss Berg, that mother of yours is bani mati” (she dares to face death).

Her death sentence was commuted to life because she was a woman. But before that, both the Kenpeitai and Political Intelligence Service tortured her severely. After two and a half years, she emerged completely gray, her teeth loose, with black-and-blue marks on her back that never faded (they had hung her by her arms). She told us how she steeled herself for interrogations: “You must look them straight in the eyes, as I learned from Father, and say fiercely: ‘Kon asu, akoe matjan’ (You are a dog, I am a tiger).”

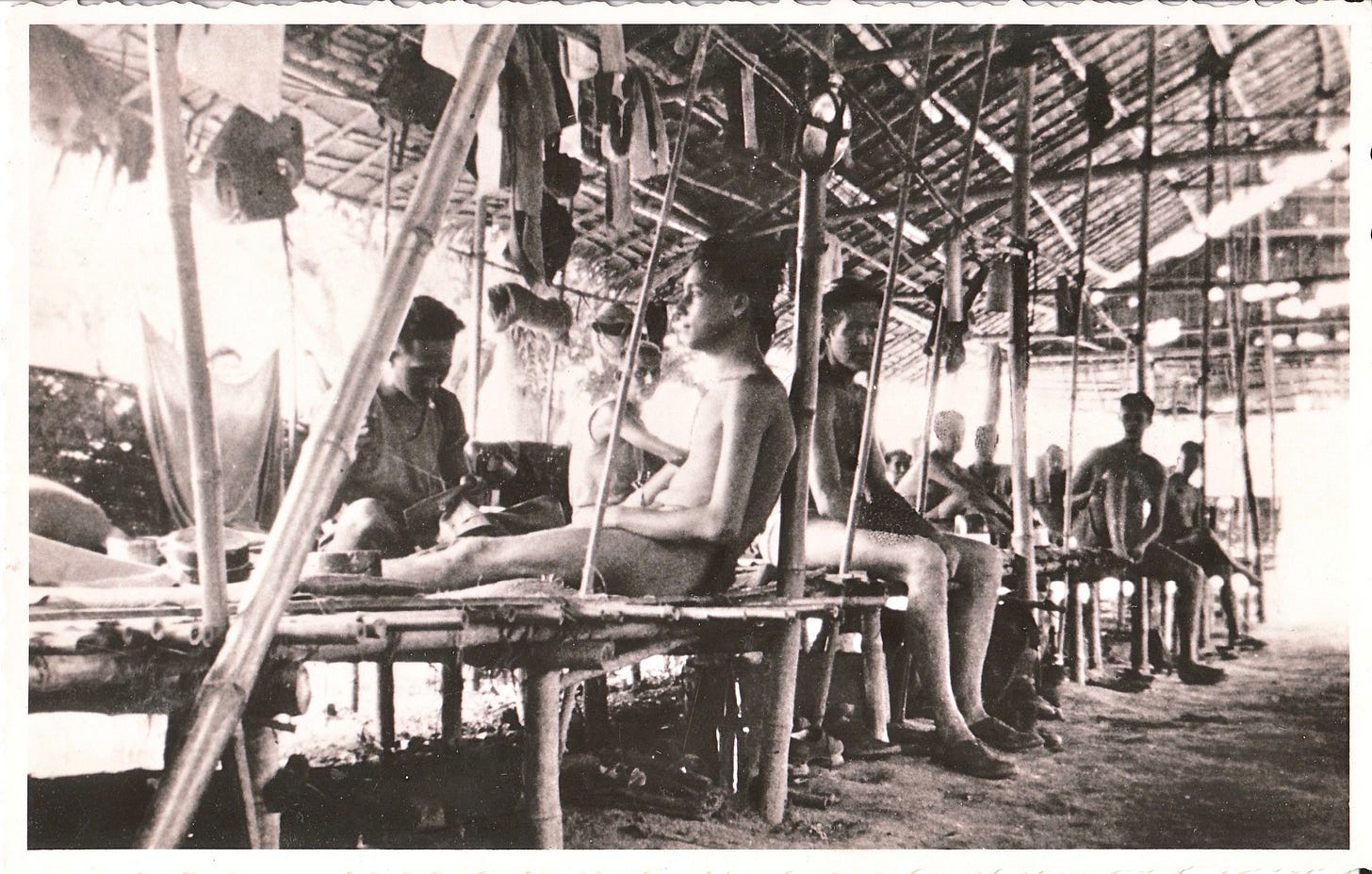

My grandfather and two uncles were sent to work on the Burma Railway—also known as the "Death Railway"—from Thailand to Burma. Around 60,000 Allied POWs and up to 250,000 Asian laborers worked under brutal conditions. About 90,000 civilians and 12,000 Allied POWs died. Camps were primitive, with 200 men in bamboo barracks and minimal food or sanitation.

Even after the railway's completion, POWs waited nearly two years for liberation. Some were sent to Japan to support wartime industry.

My father evaded capture for three months but was taken prisoner on March 8, 1942, and sent to Nagasaki on a "hell ship." He was later interned in Fukuoka, where he worked at the On'ga Mining Station. My father was hospitalized with acute colitis in April 1943.

By the end of the war, Japan had seven main camps, 81 branches, and three detached camps. Over 32,000 Allied POWs were held, mostly in mines or industrial zones around Tokyo, Yokohama, Osaka, and Kobe. As Allied bombing intensified, some camps were relocated closer to the Sea of Japan. Conditions were harsh—basic wooden buildings, barbed wire fences, straw mats, and makeshift heating.1

The Field and Dreaming Body

As Neil continued, I noticed that my chest area began to tighten. That sensation raised up to my throat and eventually into a headache on my left side. I wondered: Was this just my personal reaction, or was I feeling something larger in the field?

Arnold Mindell, in his work on process-oriented psychology, calls this being “dreamt up” by the field—when our bodies begin to express something collective, not just personal. As my grief surfaced, I sensed that more was moving through the room: unspoken pain, ancestral memories, unintegrated sorrow.

Neil apology triggered the unconscious within individuals and in the field where awarenesses began to bubble or pop up from particular participants whose ancestors were being addressed. A person of Filipino descent spoke, thanking Neil for his apology and of ancestors killed for refusing to betray neighbors to Japanese soldiers. A woman of Chinese descent shared memories of invasion and loss. Almost simultaneously, a Vietnamese participant began to wail.

Collective Trauma Healing and the Field

From Mindell’s perspective, the “dreaming field” is an underlying field of awareness that moves through body symptoms, dreams, relationships, and group dynamics. Hübl describes the field in similar terms: as a living relational system that holds both personal and collective information. When trauma goes unintegrated, the field becomes fragmented—disconnected, incoherent.

In a Collective Trauma Integration Process, we work to restore coherence in the field. Sensations, images, tensions, even numbness—these are all expressions of the field's intelligence. My sense is that Neil’s apology activated not just individual memories but something in the collective field. Awarenesses began to surface across the group as ancestral wounds were named. When we attune deeply to this shared space, the field becomes a vessel for transformation. According to Thomas, a “we-space” emerges—a form of group intelligence with the potential to catalyze healing and even evolution.

Ah dear Astrid, Thank you so much for sharing this deeply healing experience and for the work you are doing for the collective. This is the way forward for the brokenness in our world. Thank you for your tears and your brave heart. And blessings to Neil and all those who participated in this essential work.